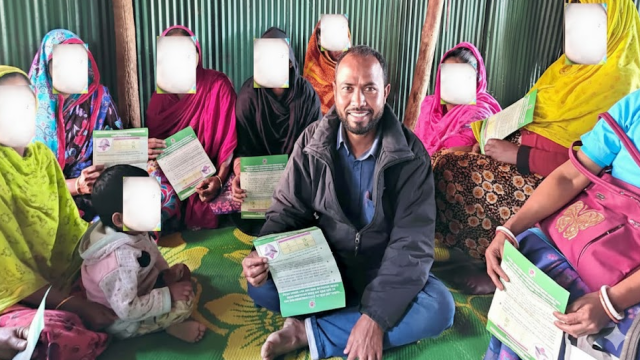

Majnu Mia, 37, now earns a living as a rickshaw driver in Dhaka's Lalmatia area after relocating from Jamalpur last year. His four-year-old son, Mishu, will never know his ancestral home, which was once located by the Dashani River but has now disappeared due to erosion. "If my son ever goes back, he’ll just see the river and realize that was our home," said Majnu tearfully. When Mishu was asked where his home is, he simply replied, "Basila."

The number of climate refugees in Dhaka is steadily increasing due to river erosion and severe droughts. Those displaced by river erosion face significant challenges as their homes vanish, leaving future generations with only memories, not addresses. Last year, severe erosion affected nine villages in Jamalpur's Bakshiganj upazila, causing the loss of cultivated land, roads, and numerous settlements to the river.

Ramisur, a hawker at Farmgate, lives in a cramped room in Tejturibazar with his nine-year-old son, Milon Sheikh. His wife works at a roadside tea shop. They once owned land and a house, but now all they possess is a bed and a few dishes. Their village community in Dhaka includes other rickshaw drivers and construction workers, whose children know their village only by name.

"When asked about his house, Ramisur said, 'In the belly of the river.' He paused and mentioned that his family once had a house in Mijanpur union of Rajbari Sadar upazila. 'I will forget the name after a few days. The children do not know that place. Their home is now this tin-and-polythene shack. The connection to our village has been severed—it will not be reconnected.'"

Thousands of settlements across the country, not just in Rajbari or Jamalpur, are disappearing due to river erosion. The new generation identifies as "Chinnamool," or rootless, as they move to Dhaka, growing up as climate refugees. If they return to their villages, they are recognized as refugees.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reports that approximately 700,000 people in Bangladesh are displaced annually by natural disasters. Cyclones like Sidr and Aila have increased this number. Since 2019, Bangladesh ranks among the top five countries for climate-induced displacement, with a 2018 World Bank report estimating that 1.33 million people could be internally displaced by 2050 due to climate change.

Climate-induced displacement is pushing people from coastal areas to cities, particularly Dhaka's slum areas. Individuals like Majnu Mia and Ramisur embody this shift, facing the challenge of redefining their children's identities for survival. Each year, Dhaka sees a growing number of climate refugees.

Sharif Jamil, member secretary of Dhoritri Rokhhay Amra (Dhora), emphasized the need for coordinated studies to determine the number of climate refugees migrating to Dhaka. "We’ve heard about one million people being displaced each year, with 400,000 coming to Dhaka. I believe the actual number is much higher, impacting Dhaka's civic amenities negatively. If this mismanagement continues, there will be no footpaths or rivers in Dhaka."

Addressing this issue requires open acknowledgment and implementation of solutions involving public participation, accurate information, and research. Climate adaptation, mitigation, and historical compensation must be prioritized, he added.

An Ever-Remaining Cycle

Case studies indicate that victims of river erosion do not always leave immediately. Conversations with residents in Basila, Paikpara, and Tejturibazar reveal they tried to survive in their villages for years, relocating their homes multiple times. When they lost everything, they moved to Dhaka, initially buying agricultural land and building houses, only to lose them to the river again. The drying river has eroded their river-dependent livelihoods.

Sharif Jamil, an environmentalist, explained that man-made and natural causes are altering the river's course, filling it with silt and turning arable land barren due to sand. "One issue affects the other. Fixing one alone won’t work; it must be addressed from the root."

Mominul Haque Sarkar, advisor of the Center for Environment and Geographic Information Service (CEGIS), noted that Bangladesh’s rivers bring significant sediment from the Himalayas, creating new grasslands and causing erosion. Ongoing erosion prevention projects can make a difference, especially during the severe erosion periods in May-June and November-December.

Psychiatrist Mekhla Sarkar highlighted the mental impact on refugee children, noting that adapting to new struggles after leaving their birthplace is very difficult. Parents' financial constraints can't meet their needs, leading to negative emotions. Early exposure to discrimination can foster fear of crime and attempts to escape it at any cost.

Comment: