For more than four decades, the impact of the Farakka Barrage has directly affected nearly two million people in the south-northern region of Bangladesh. The Padma River, one of the country's main rivers, is drying up during the dry season, causing significant environmental and economic challenges.

This year, Bangladesh received significantly less water from India than stipulated by the Ganges Treaty. During the dry season, water shortages have become evident upstream and downstream of the Hardinge Bridge in Pakshi, Ishwardi, Pabna. Once a mighty river, the Padma has turned into a small stream. Several other rivers, including Suta, Kamla, and Ichamati, have also been significantly affected, along with at least 17 more.

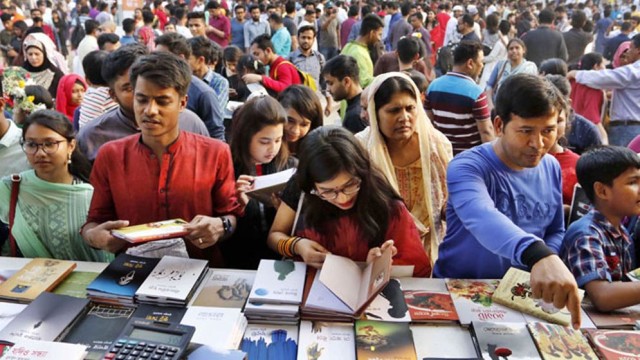

Riverbank residents and fishermen Abdur Rashid and Zainal Uddin told Voice7 News Correspondent, "A large part of the Padma River near the Hardinge Bridge point in Pakshi, Pabna has dried up. We are mostly unemployed throughout the year as there is no water like before, hence no fish. We have to find other work to survive."

The Ganges Water Treaty with India, signed 28 years ago, has rarely been fully implemented. Except for a few years, India has not supplied water according to the treaty. Meanwhile, climate change and increased water demand have further complicated the situation. Experts suggest reviewing the Ganges Water Treaty to restore the Padma and sustain the local population.

Experts believe that the drop in water levels has led to the near-death of all tributaries, including the Padma. Consequently, the environment and biodiversity along the Padma's banks have been under threat for years. Officials from the Water Development Board and the Hydrology Department indicated that the Indian delegation attributed the decreased water flow at Farakka to drought and lack of rainfall. This has similarly reduced the water flow in the Padma River at the Hardinge Bridge point in Ishwardi's Pakshi.

Sources reveal that on December 12, 1996, Bangladesh and India signed a 30-year water treaty to protect the northwestern region of Bangladesh from desertification. At that time, India's Prime Minister Deve Gowda and Bangladesh's Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina signed the historic 30-year water treaty at Hyderabad House. According to the treaty, India is supposed to supply Bangladesh with 35,000 cusecs of water from January 1 to May 31 each year.

According to the Hydrology Department of the Pabna Water Development Board, water monitoring is conducted annually from January 1 to May 31 following the Bangladesh-India joint water agreement. Joint River Commission officials are responsible for monitoring the Ganges water at Farakka Point in India, while another delegation monitors it at a point two and a half thousand feet upstream of the Pakshi Hardinge Bridge in Ishwardi.

The agreement outlines specific terms for water distribution based on the flow at Farakka. If the water flow at Farakka Point is 70,000 cusecs or less during the first 10 days, both Bangladesh and India receive 50 percent of the water. In the second 10 days, if the flow remains at 70,000 cusecs, Bangladesh is allocated 35,000 cusecs. For the third 10-day period, if the flow increases to 75,000 cusecs or more, India receives 40,000 cusecs, with the remaining water allocated to Bangladesh.

Additionally, the agreement specifies that from March 11 to May 10, both Bangladesh and India will each receive 35,000 cusecs of water in three 10-day periods, ensuring a fair distribution during this critical time.

Data from the Hydrology Department of the Pabna Water Development Board shows that on May 24, the water flow at the Pakshi Hardinge Bridge point was recorded at 29,169 cusecs. On the previous day, May 23, it was 26,656 cusecs.

Executive Engineer of the Hydrology Department in Pabna, Raich Uddin, told Voice7 News, "On May 16, a delegation from the Indian River Commission, including member and executive engineer Aparva Raj and Sudipta Mahanti, observed and measured the current water flow at the Pakshi Hardinge Bridge point of the Padma River. They informed us that they would monitor the water flow daily until May 31."

Indian River Commission member and executive engineer Aparva Raj told Voice7 News, "Due to the low water levels, the flow at Farakka is being split, with half being allocated to Bangladesh. The flow will gradually increase."

River researcher and analyst Professor Abul Kalam Azad from Ishwardi's Pakshi said to Voice7 News, "Rivers need to be allowed to exist naturally. If not, the environment and nature will slowly be destroyed, adversely affecting the world. It's crucial to review the Ganges Water Treaty now."

Environmental expert and former head of the Department of Botany at Government Edward College, Professor Shahnewaz Salam, told Voice7 News, "The adverse effects of Farakka still threaten the environment and biodiversity. The Padma no longer has the same water levels, causing a widespread water crisis. I believe a new Ganges Water Treaty is needed to address these issues."

Amitabh Chowdhury, executive engineer of the Northern Region Water Measurement Department and the Pabna Water Development Board said, "According to the 1996 treaty, India is supposed to provide Bangladesh with 35,000 cusecs of water. Currently, we are receiving less than that."

END/V7N/SRP/SMA/DK/

.jpg)

.jpg)

Comment: