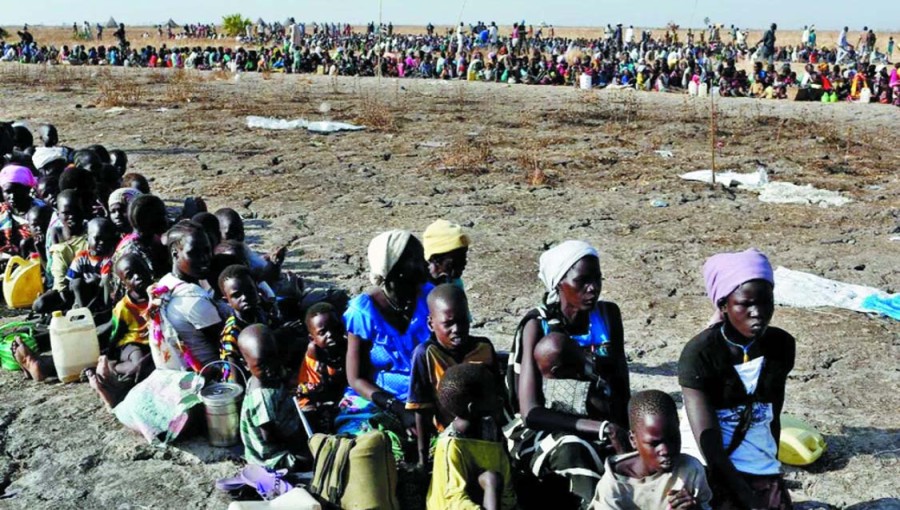

Halving food waste could cut climate-warming emissions and end undernourishment for 153 million people globally, the OECD and the UN's food agency said in a joint report Tuesday.

Around a third of food produced for human consumption gets lost or wasted globally, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization -- resulting in useless emissions and less available food for those who need it.

By 2033, the number of calories lost and wasted between produce leaving farms and reaching shops and households could be more than twice the number of calories currently consumed in low-income countries in a year, the report warned.

Cutting in two the amount of food lost and wasted along the journey from farm to fork “has the potential to reduce global agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by 4% and the number of undernourished people by 153 million by the year 2030,” according to the report. “This target is a highly ambitious upper bound and would require substantial changes by both consumers and producer side,” they added.

Agriculture, forestry and other land use account for around one-fifth of global human-induced greenhouse gas emissions.

UN nations have committed to cutting per capita food waste by 50% by 2030 as part of sustainable development goals but there is no global target for reducing food loss along the production supply chain.

Between 2021 and 2023, fruit and vegetables accounted for more than half of the lost and wasted food given their extremely perishable nature and relatively short shelf life, according to the report.

Cereals followed, accounting for over a quarter of lost and wasted food.

Halving food loss and waste by 2030 could result in increased food intake by 10% for low-income countries, 6% in lower middle-income nations and 4% in upper middle-income ones, it added. A UN-led meeting with Afghanistan’s Taliban will be held in the Qatari capital Doha this weekend, in which representatives from some 25 countries are expected to take part. It will be the third such meeting, but the first attended by the Islamic fundamentalist group which has ruled the war-torn nation since it seized power as US-led troops withdrew in August 2021.

The UN political chief who will chair the meeting said it’s not about granting recognition to the Taliban.

“This is not a meeting about recognition. This is not a meeting to lead to recognition... Having engagement doesn’t mean recognition,” UN Undersecretary-General Rosemary DiCarlo told reporters. “This isn’t about the Taliban. This is about Afghanistan and the people.”

Achieving sustainable peace, adherence to international law and human rights, as well as counter-narcotics efforts, among other things, are on the agenda of the talks, DiCarlo said.

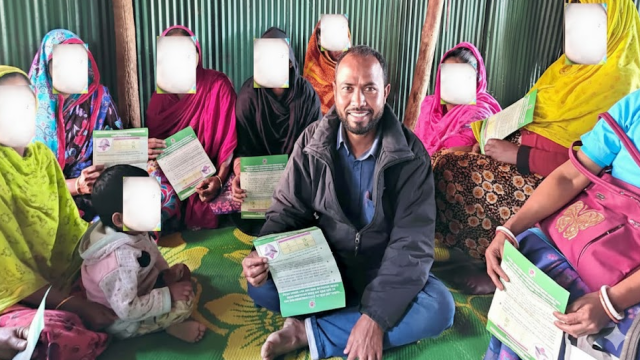

The Taliban side has said it wants to discuss topics such as restrictions on Afghanistan’s financial and banking system, development of the private sector and countering drug trafficking. But rights groups have denounced the UN for not having Afghan women at the table with the Taliban in Doha. Shabnam Salehi, former commissioner of Afghanistan’s Independent Human Rights Commission, said the third Doha meeting would be “inconclusive” without Afghan women’s participation. She views the UN’s approach toward the Taliban as “misguided.”

Faizullah Jalal, a professor at Kabul University, has slammed the exclusion of women from the meeting. “Omitting discussions on human and women’s rights undermines the United Nations’ credibility,” he said.

His view is shared by Tirana Hassan, executive director at Human Rights Watch. She warned that excluding women “risks legitimizing the Taliban’s misconduct and irreparably damages the United Nations’ credibility as a defender of women’s rights and meaningful participation.” But the UN’s DiCarlo said the two-day meeting, starting Sunday, is an initial engagement aimed at initiating a step-by-step process with the Taliban.

The goal is to see the Taliban “at peace with itself and its neighbors and adhering to international law,” the UN Charter.

, and human rights, she stressed.

“I want to emphasize — this is a process. We are getting a lot of criticism: Why aren’t women at the table? Why aren’t Afghan women at the table? Why is civil society not at the table? This is not an inter-Afghan dialogue,” said DiCarlo. “I would hope we could get to that someday, but we’re not there.”

After drawing much censure, the UN has decided to hold a separate meeting with Afghan civil society in Doha next week.

Taliban banish women from almost all public life

Since seizing power, the Taliban have rolled back progress achieved in the previous two decades when it came to women’s rights.

They have banished women and girls from almost all areas of public life.

Girls have been barred from attending school beyond sixth grade, and women were prohibited from local jobs and nongovernmental organizations. The Taliban have ordered the closure of beauty salons and barred women from going to gyms and parks. Women also can’t go out without a male guardian.

In a decree issued in May 2022, women were also advised to wear a full-body burqa that showed only their eyes.

The oppression of women’s rights means no country has so far officially recognized the Taliban as Afghanistan’s government. The United Nations has said recognition is almost impossible while bans on female education and employment remain in place.

No recognition for the Taliban

Countries around the world have made any engagement with Afghanistan conditional on the Taliban improving things such as girls’ access to education, human rights and inclusive government.

But the militant regime has so far not shown any signs it is willing to drop the hard-line policies.

Activists have said that achieving any meaningful progress at the meeting hinges on fair and transparent representation of all relevant groups, including women.

They also stress that the international community needs to immediately address the Taliban’s grave rights violations.

Agnes Callamard, secretary-general of Amnesty International, said of the Doha meeting that “sidestepping critical human rights debates is unacceptable.”

“Afghans, especially women, must be given spaces at the table to advocate on their own behalf,” Rina Amiri, US special envoy for human rights and women’s affairs in Afghanistan, wrote on the social media platform X. “Afghanistan’s peace, security, and sustainability challenges cannot be resolved without their inclusion.”

Comment: