In the 1990s, substantial investments were made by charities, governments, and philanthropists to combat malaria, aiming to reduce global malaria deaths by 50% by 2010. At that time, malaria posed a significant threat, claiming the lives of approximately one million people annually, primarily children.

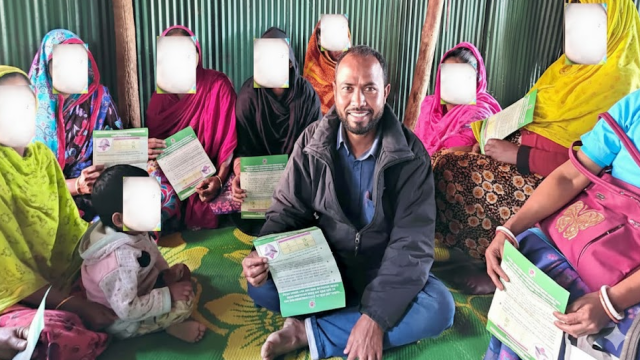

The "Roll Back Malaria" campaign, launched in 1998, received substantial funding from global organizations like the World Health Organization and the World Bank. Efforts included distributing mosquito bed nets, indoor insecticide sprays, and introducing new drugs to combat chloroquine-resistant mosquitoes.

These initiatives successfully halved malaria deaths in less than twenty years. However, progress stagnated around 2015, followed by a notable increase in malaria cases globally by 2020. In 2022, global malaria cases surged to over 248 million, up from around 230 million in 2014.

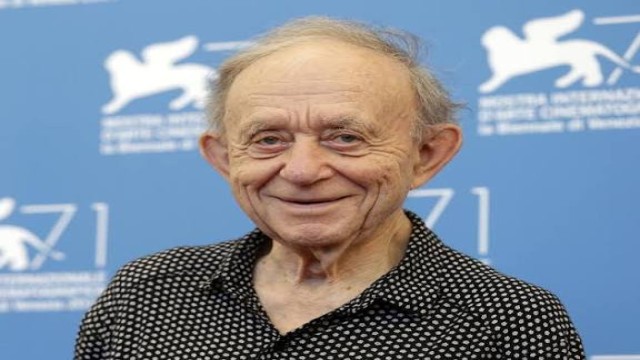

The response to this setback prompted malaria scientist Nicholas White to question the World Health Organization's data, suggesting that despite significant investments, malaria cases hadn't decreased. The WHO countered, attributing the apparent stagnation to factors such as global population growth and ongoing challenges in sub-Saharan Africa, including reduced funding and limited access to quality care.

Experts point to the rapid adaptation of malaria-spreading mosquitoes to interventions as a significant challenge. Mosquitoes have developed resistance to insecticides, while the parasite causing malaria has become resistant to treatment drugs in some regions. Moreover, the emergence of the Anopheles stephensi mosquito in East Africa, capable of spreading malaria in urban areas, presents a new threat.

Despite these challenges, funding for malaria research and development has decreased, reaching its lowest level in fifteen years in 2022. While vaccines, such as the RTS,S and R21/Matrix M, offer hope, experts caution that they are not a singular solution to malaria control.

Comment: